In a world of easy travel it’s not surprising that some highly photogenic locations feature heavily in the media, travel itineraries, on photo workshop itineraries and photo competitions. This visibility in turn attracts more photographers to get ‘the shot’ – often the same shot or the picture postcard version. In this series we investigate how to retrain our eyes and minds into thinking differently in over-photographed places. In this instalment we visit the Taj Mahal in India.

Where is the Taj Mahal?

India – in the city of Agra in the state of Uttar Pradesh. It’s only about two hours by train from the capital Delhi and easily accessible to visitors from around the world – a highlight on the Golden Triangle tourist itinerary.

What is it?

A masterpiece of architecture and a homage to love…and loss. Whipped-cream turrets petrified in marble on a grand scale, flanked by a quartet of imposing minarets, all intricately chiseled and decorated with semi-precious stones by the Mughal empire’s finest craftsmen. It was built as a mausoleum for Mumtaz Mahal, created by her grief-stricken husband the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, to commemorate her death in childbirth. It’s a kind of belated and permanent Valentine’s card in white marble.

How did it rise to stardom?

More of a rise and fall followed by a bit more rising. And rising. It took more than 20,000 craftsmen 22 years to build and was finally unveiled in 1653. A couple of centuries of family quarrels, warring neighbours and subsequent looting saw the complex eventually fall into unrecognisable disrepair by the late nineteenth century. Its restoration was commissioned by British viceroy Lord Curzon in the early 1900s and by 1983 it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its fame got a boost in 1992 when Princess Diana posed alone in front of it a short while before the demise of her marriage to Prince Charles. In 2000 the Switzerland-based New 7 Wonders Foundation set out to update the Wonders of the World list (because only one of the original seven is still standing) and a global public vote unveiled in 2007 saw it crowned alongside six other bucket list staples .

What do the typical pictures look like?

The most common shots show the central dome and minarets taken from the visitor entrance with the long stretch of water and fountains in front.

The marble changes colour throughout the day as the sunlight refracts and bounces among the multiple micas, quartzes and oxides in it. Dawn and dusk are popular as the white stone contrasts with the pinky hues of the early morning. Sunrise is even more of a favourite as the stone takes on warm, golden tones against a brilliant blue sky. If you queue up at the crack of dawn, you might make it into the complex before sunrise at certain times of year.

Like many architecturally perfect buildings, there are many vantage points from which you can point your camera to create a sublime image. But is it your creativity or the architect’s?

The front vista is designed to be entrancing and sublime; the majesty of the building is reflected in a perfectly placed pool of water leading your eye (and subsequently your feet) towards the tomb itself. This, along with the perfect symmetry of the design, is a point-and-shooter’s dream.

What’s the problem?

The crowds, lots of them! It’s not just people standing in the way of your shot but everyone else who’s had the same idea and taken the same shot from that spot. A guide will be able to show you other well-worn vantage points from which to shoot but you’re just doing the architects’ bidding; they designed it to be viewed from these perspectives.

If you want a shot inside the complex, be prepared to be patient. There will be gaps but they won’t be frequent and you’ll have to act quickly when they appear. However, you need to accept that, unless you are very creative, then you’ll end up with more of a picture postcard than a masterpiece.

Chris Coe, TPOTY founder and judge says “We see a lot of views that are obvious or taken from easy-to-reach viewpoints, so part of your creative process is to explore and find other ways of seeing. On their own these viewpoints have probably also been photographed before but, in combination with the choice of time of day and changing light, you can still create something unique.”

“A pale-coloured marble structure loses a lot of its subtlety and detail in intense Indian sunlight,” says Chris, “However, shooting at the extremes of the day – very early morning or after sunset, dawn or dusk, can make your photographs come alive. You may not have access to the complex at these times but you can still find viewpoints which work and give you something creative and interesting.”

“Shooting at the extremes of the day can make your photographs come alive”

Are there winning shots of the Taj Mahal?

Yes! Paul Sansome’s shot, part of his winning Art of Travel portfolio in 2019, was a favourite of the judges. The perspective itself is head-on and familiar but by using multiple exposures (not photoshop) he brings a mystical sense of movement to the scene yet without the movement or the crowds, detracting from his image. Rather than cursing the crowds and avoiding them he used them to his advantage.

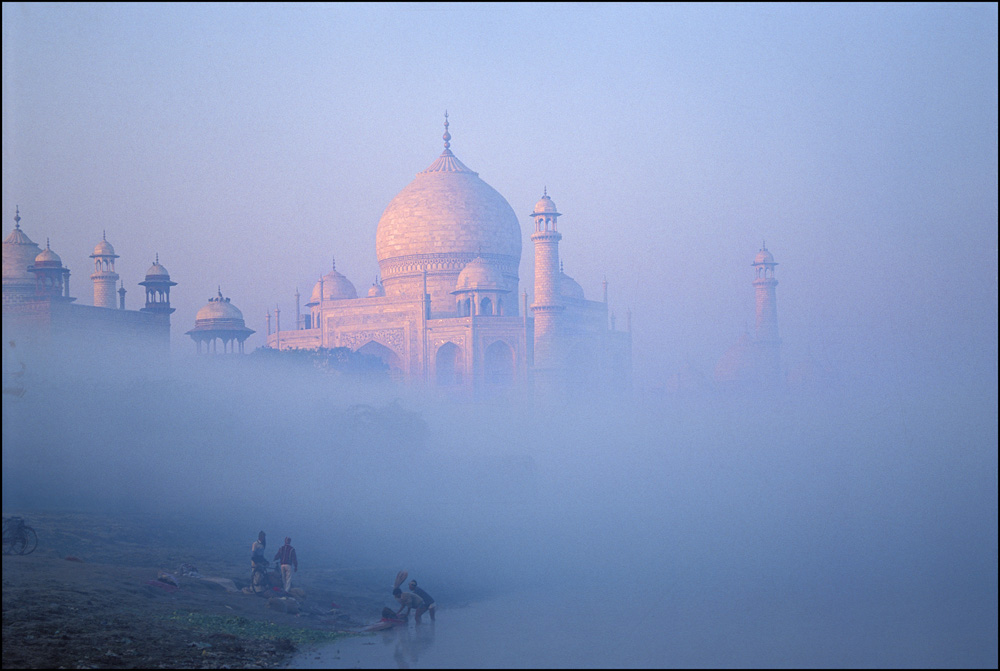

Karoki Lewis’s shot taken at dawn won a category prize in 2004. He nicely negotiated the problem of opening hours by hopping over to the other side of the complex where you can see the building, sitting of the banks of the Yamuna river, at any time of day and without an entry ticket. As well as finding a new perspective, he coupled it with soft perfect light.

Chris says “The combination of an alternative viewpoint with soft dawn light creates a wonderful atmosphere which enhances the imposing structure of the Taj Mahal and shows the subtleties of both colour and form. There will be viewpoints where a composition works equally well at the end of the day, too, or you may like to consider the natural lighting of a full moon as an unusual alternative.”

Where else could you shoot nearby?

If you find yourself exasperated by Agra’s crowds, take a taxi 30km west to Fatehpur Sikri. It was built as the Mughal empire’s capital city but quickly abandoned in part because there was no natural and enduring source of water. The complex itself predates the Taj by a century or so but is another fine example of Mughal architecture. It’s a beautifully preserved series of red-sandstone palaces and pavilions and, while the sandstone doesn’t have the alluring milky quality of the marble, it also doesn’t have anything like the crowds and legacy of popularity of the Taj.

With thanks to photographer and India expert Tim Bird for insider knowledge, photos and help writing this piece.