Florian Ledoux is originally from France but spends much of the year in the polar regions. He’s exclusively a polar photographer and has learned how to overcome the harsh, freezing conditions at the ends of the earth in order to create images that capture the characters as well as the perilous predicament of the creatures who live there.

One of his most well-known images shows a polar bear among blocks of ice, shot from above using a drone. “During this long expedition, as the result of long hours of work, I took this aerial image of the polar bear leaping across the melting ice of the Arctic during summer. It’s a perspective that hadn’t been seen before and has a strong message as it’s at the crossing point of the three important strands of my work: creativity, conservation and science. The image gave me the opportunity to bring the entire message of my work to the public and created a lot of important connections and awareness.”

The shot was published worldwide in Time Magazine, National Geographic, Oceanographic UK and won a lot of awards including Grand Prize Drone Photography of the Year 2017, Drone Photographer of the Year 2018, prizes in conservation competitions as well as runner-up in the Endangered Planet category of TPOTY 2018. It was also shown at the fine art exhibition in the Louvre.

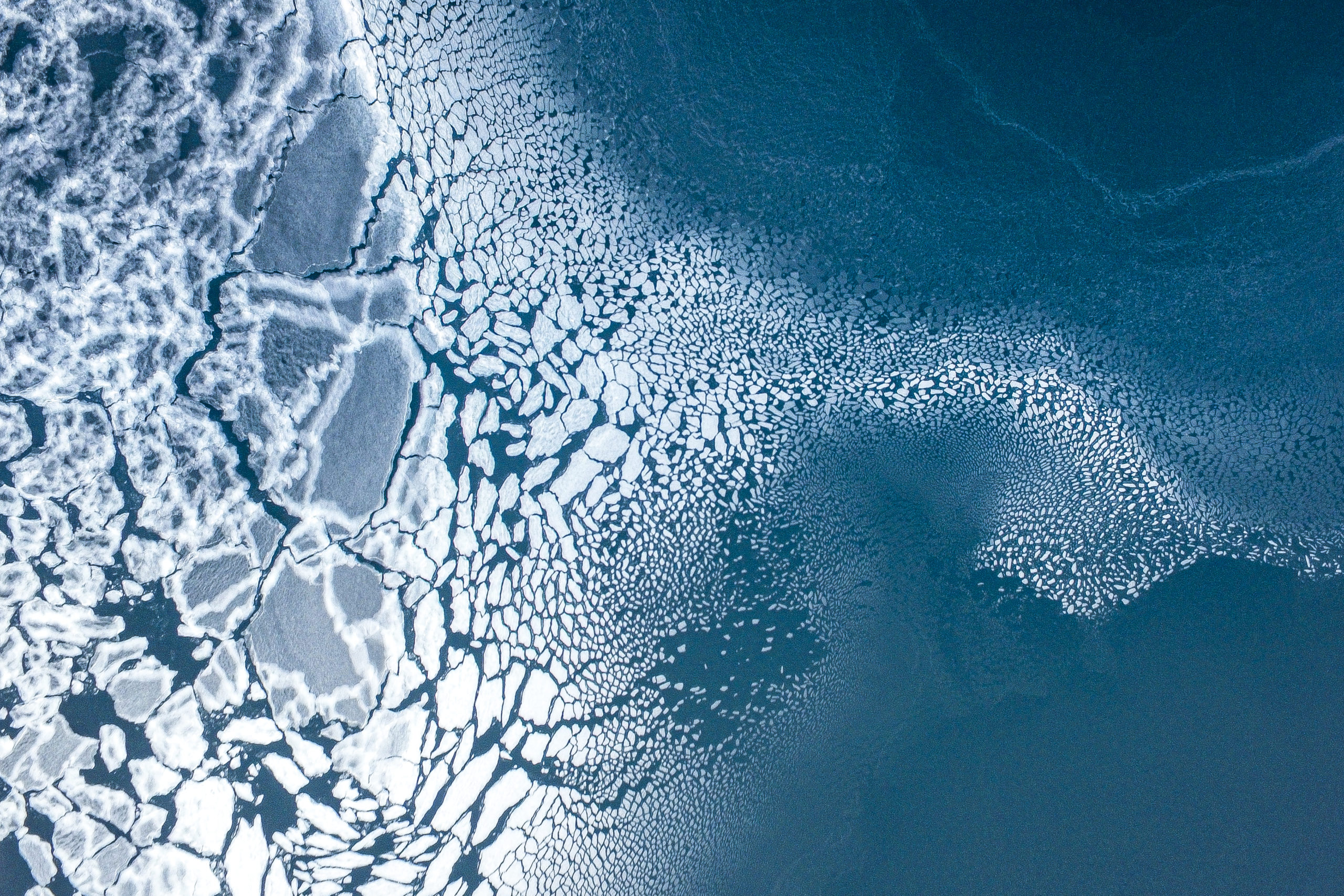

The image is striking for its bold shapes and simple colour palette but the artistry comes in no small part from the delicacy and lace-like quality of the receding summer ice.

“Of course, it was then important to create more of these storytelling images,” says Florian, which is exactly what he achieves in the rest of the series that won him the TPOTY award.

“A new way of learning about the white northern part of our planet”

“Seeing the world from this perspective helps us to understand how its inhabitants – extraordinary species – are able to live in one of the most hostile and difficult places on the planet and how they rely on the ice to survive. These images show us the unreal beauty drawn by nature – the power of it – but also how fragile this ecosystem is. They allow us to observe and document animal behaviours from new angles, revealing the animals in their entirety as well as in a wider habitat and landscape, in a way not before possible, a new way of learning about the white northern part of our planet – a world that I hope we can protect as it bears a crucial role for the rest of life on earth.”

The images were taken on a once-in-a-lifetime sailing expedition from Greenland to Nunavut that Florian took after quitting his job as a helicopter technician in the navy. It was a life-changing trip after which he made a commitment to protect the natural world through photography. It wasn’t a sudden realisation, it was something that had been growing for many years.

“Photography came as a result of my love and passion for the natural world. When I was younger, I always felt a strong connection with nature, which made me want to share it with my family and friends. The camera became a tool to capture and witness the beauty of nature. Later on, I realised how powerful one image can be and decided to commit to my passion and create meaningful photographs which have impact and could gain attention for the issues they reveal.

“Nature is everything to me, it’s the place where I feel connected to the rest of the world. I have a mind full of questions – what is life’s purpose? Who are we as humans? How can the natural world be so perfectly balanced and in harmony? Nature is the place where it all makes sense, the place where I find my answers. It feels like it’s where it all began! These are our origins. Not only do we come from nature but we are part of this complex ecosystem, the mysterious equation called ‘Life’.”

The transition from helicopter technician to conservation photographer was also not an overnight transformation: “While working in the navy, photography was already part of my life. In 2014 I applied to become a photographer and cameraman in the navy, and I was already committed in my love for nature. I undertook my first expedition to Greenland the same year and my work on photography outside the navy kept growing. I invested a lot of my own time and money, but this is the call for my passion so I just kept going back to it.

“In one way I was eager to learn more and discover how I could do justice to the beautiful world I saw. I was just following my heart. After years of perseverance, building a network and looking for opportunities, I quit the navy and became a full-time photographer”.

There was additional inspiration along the way from world-renowned photographers: “When I was younger, I was inspired by a few photographers. The message and aerial aesthetic of Paul Nicklen’s images was definitely a source of inspiration in my quest for creating different images. Later I was very inspired by the powerful storytelling of Ami Vitale’s work. The French photographer Vincent Munier contributed to nourishing my mind towards nature with his naturalist and minimalist approach to the natural world, but also the likes of Sebastião Salgado and Jim Brandenburg were important in my development as a photographer. Lately in my career, I have been very grateful to meet or see my work amongst those mentors that shaped my mind and eyes.”

Photography in cold climates

“My work is all focused on the polar regions. I like both the Arctic and Antarctica, probably equally but in different ways. I love those regions of the planet for their immense landscape and nature, which remains wild and almost untouched by human activity. You can sail, hike and explore for several months without witnessing any sign of humanity. The scale of those landscapes and the fascination for the incredible species living there at the edge of the ice drew me there. I was ten years old when my parents took me on my first journey above the Arctic Circle and I was deeply and emotionally touched by the experience; this feeling is something that is still growing in intensity as I explore further and wilder.”

The practicalities of flying so far north into such cold places comes with its own set of challenges. “It’s totally different and this is even truer when you want to approach wildlife. There can be a lot of issues with magnetism, lack of GPS and it can be very tricky and risky. I crashed a few drones while producing images in the past.

“Nowadays after more than 950 flights in those regions, I have gained enough experience in order to handle the situations. Also, drone technology has improved a lot and allows us to push the boundaries. This winter I flew a lot in -45°C and another limitation is that our human body is not designed to be in the cold in the way that Arctic wildlife has adapted to it. Every shot is a battle with our own limitations, but also a moment where you feel nature is giving it to you.”

In May 2019, Florian returned to Greenland as part of the Arctic Arts Project along with four fellow photographers and a remit to find visual evidence of the latest scientific finding on climate change in Greenland.

The two-week science expedition to Western Greenland revealed many of the dramatic changes scientists have been quantifying in recent research papers. This allowed Florian and his teammates to document visually what the science has revealed and to share it with the public.

The team met leading climate researcher Jason Box in Copenhagen who gave them some alarming data: “2019 is setting up to be a very high high-melt year for Greenland due to several factors; thin snow cover from a dry winter and melt starting three to four weeks earlier than usual. These conditions at the start of the melt season allow the albedo feedback to maximise its impact.” Albedo is Latin for “whiteness” and the effect is the earth’s ability to reflect heat from the sun back into the atmosphere. Lighter surfaces like the polar regions reflect more heat back which keeps the planet cooler.

The warm weather after a dry winter has a swift and meaningful impact on meltwater coming off the great ice sheet that covers so much of Greenland. In a flight over the western side of the ice sheet the team saw huge amounts of blue in this usually endless expanse of white. The albedo effect changes dramatically when a surface is no longer white. More of the sun’s energy is absorbed by darker surfaces. This, in turn, causes more ice to melt and increases the amount of water that will flow into the ocean.

The team was stunned by the immediate effects of an early, warm spring; they saw temperatures of 16ºC (60ºF) in Ilulissat. “People were wearing shorts and sundresses where normally their parkas and boots would still be needed in late May. The sea ice was nearly gone when dog sledges would normally still be running along with it.”

Florian has taken many more expeditions across the polar regions and has become known for his aerial images of the colder parts of the world. He was involved in some major projects and has published in the books that accompany TV series including the BBC’s Perfect Planet, Netflix’s Our Planet and BBC’s Seven Worlds, One Planet.

“If we were part of the natural world, we would not destroy it.”

“Images are a universal language that speaks to all of us, no matter our tradition, religion, or language. They connect us emotionally. We need to reconnect people to nature if we want to solve the major issues we are now facing. We need to live in balance and harmony with the planet and stop harvesting it. If we were part of the natural world, we would not destroy it.

“Photography and films can help us to understand the challenge we are facing. It is hard to estimate the direct impact on people and the way it affects them, but the work carries a message. I often collaborate with scientific or conservation organisations with images that they use for their outreach or projects. I don’t work directly on projects in the field but closely collaborate on projects like the one in Greenland. I believe science and image-makers should work more together as they have the data and facts and we have the images to communicate it.”

What’s next for Florian Ledoux?

In September he’ll be giving a speech at the World Conservation congress organised by the IUCN in Marseille followed by a return to Svalbard with M/S Polar Front. “I would love to publish a major artistic book about the polar regions. But I’ve also had many more ideas of projects I want to do, like wintering in some very special location in the sea ice. The purpose is always to live closer to the animals I want to document because in that way you feel and think like them. Individuals eventually become friends.”

Florian’s journey into and through photography is an inspiring one, especially for anyone interested in conserving our planet. We all have dreams and passions but too often don’t follow them. He concludes: “One thing I’ve learned over the years is that the best thing to do, not only in photography but anything you want to achieve in life, is to just do it with passion and follow your heart.”

For more info, visit florian-ledoux.com