Craig Easton started off as a press photographer for the Independent in the early 1980s but it was his desire to tell longer-form stories that led him to documentary work. He’s worked extensively around the British coast for the last 25 years or so and has won two TPOTY awards with the resulting images.

In 2012 Craig Easton scooped the title of Travel Photographer of the Year with portfolios which included photos made in Skye, the Outer Hebrides and Paris and in 2016 he won the Land, Sea, Sky category with a series of shots taken near his home on the Wirral peninsula in northwest England.

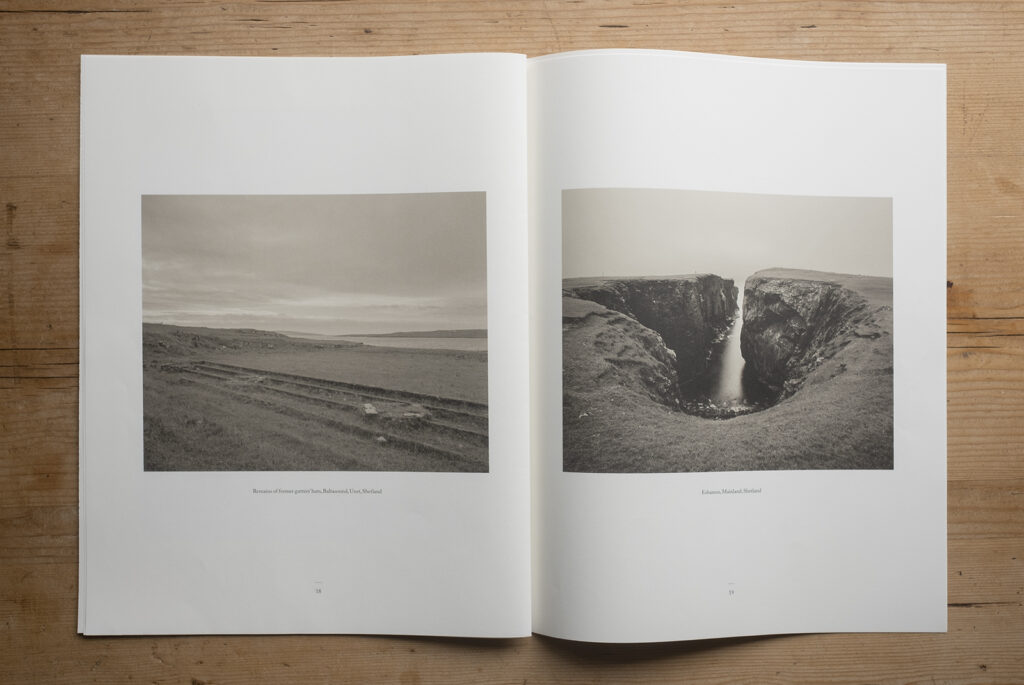

His familiarity with the coast led directly to his latest project in which he followed the route of the traditional herring fleet from Shetland to Great Yarmouth. The project combines large format portraits and landscapes with anecdotes from the people he met along the way to weave a narrative of a unique history of British working women.

What inspired the project?

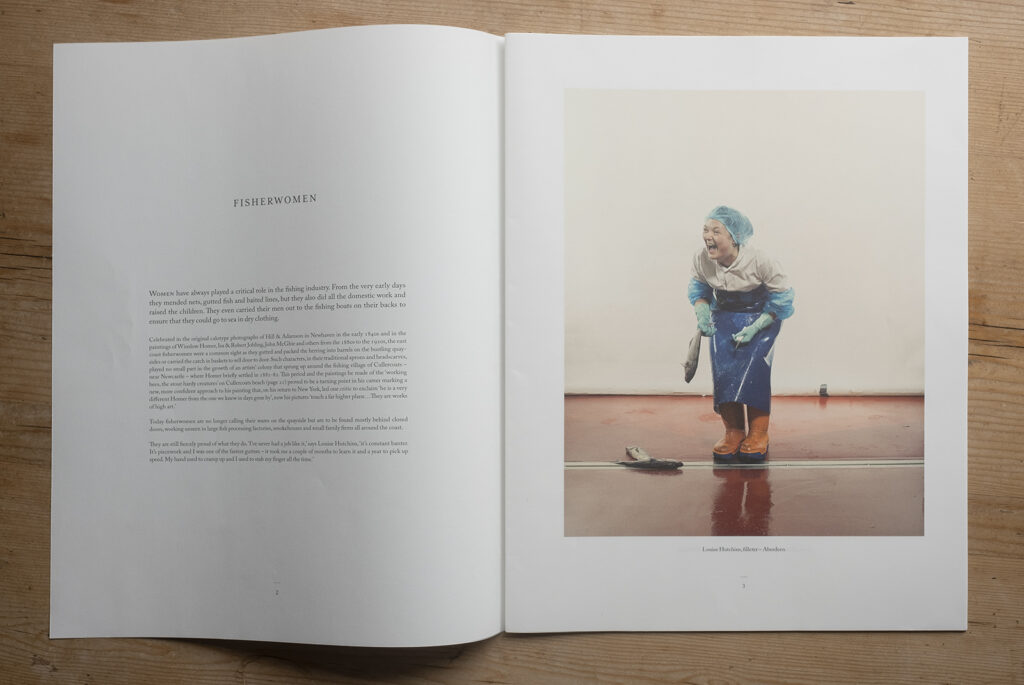

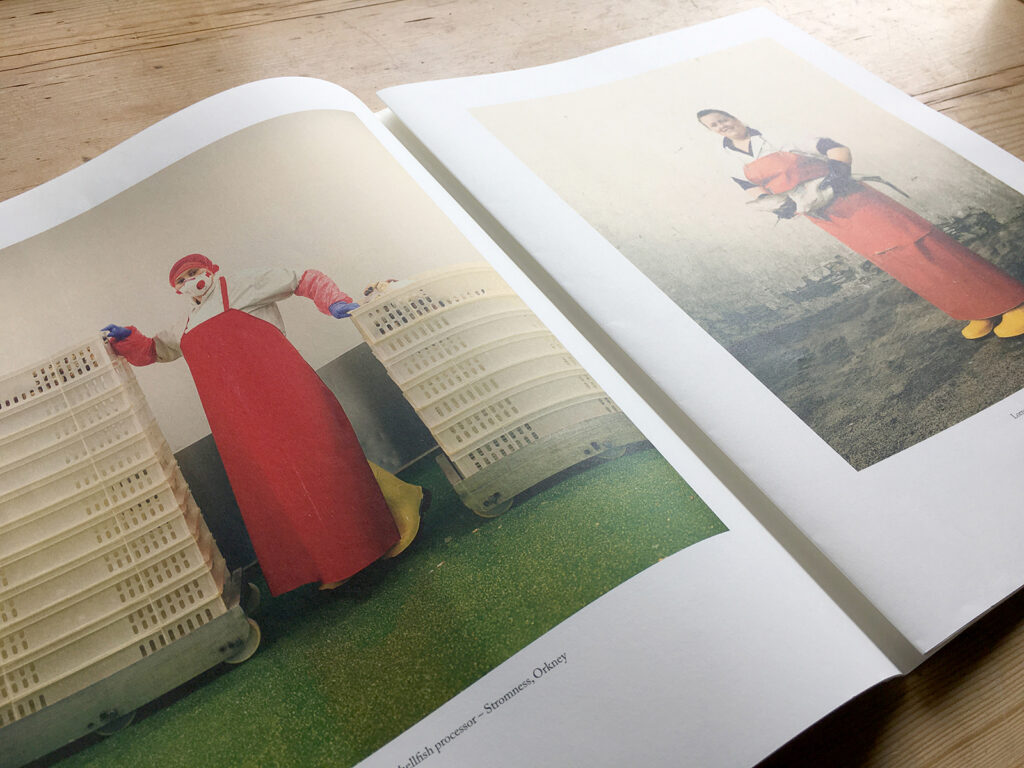

I was aware of the story of the ‘herring girls’ from pictures and postcards that showed women up to their elbows in fish; gutting and packing them into thousands of barrels on the quayside. I was also familiar with the paintings of Winslow Homer – regarded as one of America’s greatest nineteenth-century painters who lived for a time in the artists’ colony around Cullercoats in Tyne and Wear – and John McGhie in Fife, both of whom had made paintings of fisherwomen. I was thinking about this work and the representation of women in fishing and just got to wondering who is doing that work now? And of course the answer is still women, but nowadays they’re no longer plying their trade outdoors on the quaysides or in herring yards but behind closed doors in fish processing houses and factories up and down the coast.

How long did it take you to get all the material needed for the book?

The project has evolved over seven years. I first started making the portraits of the contemporary fish workers in 2013, just knocking on doors of fish factories and smokehouses and small family firms in Aberdeenshire. The idea slowly evolved into what it became: a three-part exploration and celebration of the contemporary and traditional importance of women to the fishing industry.

The key for me was to connect the contemporary experience to the great tradition of mothers and daughters ‘going to the gutting’ and I wanted to put the spotlight back on the women themselves. Early photographic pioneers David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson made portraits of fisherwomen in Newhaven near Edinburgh in 1843 and these are widely considered to be the first social documentary photographs ever made anywhere in the world. (I’ve also included a supplement accompanying the portfolio that examines the shared history between photography and fisherwomen.) And then of course the Homer paintings in the north east. In each case the subject of the photograph or painting was the fisherwoman herself – they were not incidental to the images, they were the central character.

I wanted to show modern fisherwomen in the same light, to celebrate and honour the extraordinary hard work and the essential contribution they make to the industry – something that is too easily forgotten when we think of fisher ’men’, those heroic characters going out on the trawlers to bring in the catch. And it seemed to me that for the best part of 100 years the focus had been on the men and there are countless photography books and photoessays about fishermen.

Did you follow the old herring fleet route in one trip or over a number of trips?

The idea to follow the traditional route of the herring fleet came to me a little later on, in 2015 or 2016. This is how projects evolve. I’d made the initial portraits not just in Aberdeenshire but in Fife and East Anglia too. But I was looking for a way to bring the project together in a cohesive way. It was then that I started making the large format black and white landscapes and the portraits of the former herring girls to create the three parts of the project. Over the seven years, the work involved numerous trips back and forth along that route. I’d spend a week in Shetland then a few days in Newcastle, or a week in Hull, then back up to Orkney – as with all personal projects it had to fit in around other work and as my research and connections grew, I’d go back to places again and again to meet different people, or to work in different weather for the landscapes.

The book also features personal testimonies from the subjects – it must have been fascinating for you to hear their stories?

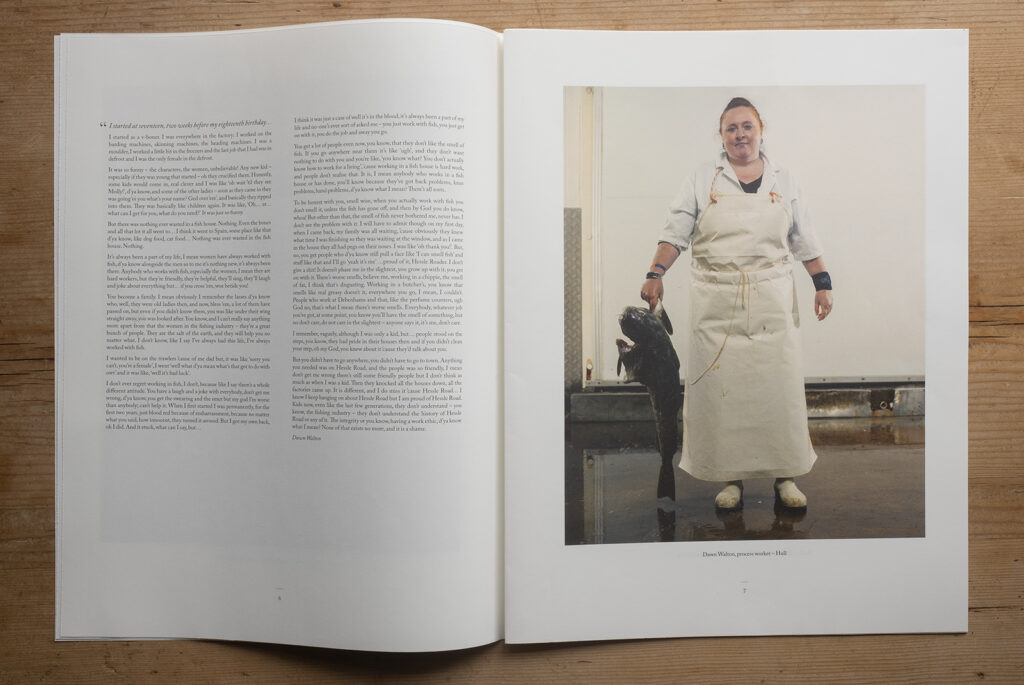

Not only fascinating but a joy and a privilege. I have such great memories of afternoons spent with some of the former fisher lassies – now in their 80s and 90s – listening to them tell tales of their youth and seeing their faces light up as if they were still sixteen and heading off on the journey south for their six-month trips. The women used to work in crews of three: two gutters and one packer, and in Whalsay in Shetland I met a number of crews who were still best friends seventy years after they first went off together as young women. So I made audio recordings too and it’s an honour to hear these stories, but I also see it as a responsibility. It’s a cliché to think of documentary photography as a ‘first draft of history’, but I do see what we do as important in that respect – we are documenting the world and it’s important that this stuff is recorded – some of the stories I recorded will be gone forever if somebody doesn’t take the trouble to remember and write them down.

Did you get a sense of how their working lives have changed and are still changing?

There is an obvious sense of their working lives having changed from the way they were when the gutting was all done by hand and packed into barrels. Nowadays it all happens in super-clean factory environments and when I show some of the older women the pictures of the contemporary processors they fall about laughing at the health and safety wear. Of course in the smaller family firms and smokehouses it hasn’t changed much at all and certainly the raucous banter and humour that fisherwomen were famous for is still there. It’s funny, looking at some of my pictures, to think that but for the rubber boots and plastic aprons some of them could be straight out of the Hill and Adamson pictures of the early 1840s – nothing’s changed and the character is still evident in the faces.

The photographs have been exhibited – where were they shown, and will there be any more exhibitions?

They were first shown in spring 2019 at The Montrose Museum and Art Gallery in Angus in Scotland. From there there was a big show at The Maritime Museum in Hull in the summer and autumn of 2020. This year’s shows of course have all been postponed due to the pandemic, but the Time and Tide Museum in Great Yarmouth are showing the work from July till September 2021. There will be exhibitions in Cromer, Newcastle, The Scottish Fisheries Museum in Anstruther announced in due course and the show in Shetland will be in 2022. Of course all this is being rescheduled now, but the work looks like it will be touring for the next couple of years – there is a show in the US pencilled in for 2021 too.

Do you have any other projects in the pipeline at the moment?

Yes, I’m one of those photographers who always has three or four projects on the go all at the same time – they’re usually inter-related in some way and are usually at different stages of development. A lot of my work is research based and I try to dig deep into stories – it not just about the pictures, it’s about using photography to investigate, learn about and document aspects of society that fascinate, inspire or incense me!

How have lockdown and Covid restrictions affected you?

I didn’t really do any shooting during the first lockdown but it was a great opportunity to catch up on some research and reading. I’m working on a project called ‘Bank Top’ about an area of Blackburn so I spent my time researching that. It’s a the result of a collaboration with writer and academic Abdul Aziz Hafiz and small, tight-knit community in Blackburn challenging, as Aziz puts it, the “simplistic representation of Blackburn and the callous use of the word ‘segregation’ by policymakers and the media when they try to explain the challenges faced by such neighbourhoods and towns.” I’m looking at issues around social deprivation, housing, unemployment, immigration, representation as well as the impacts and legacy of contemporary and colonial foreign policy. I’ve also regularly visited the local marine lake with the camera.

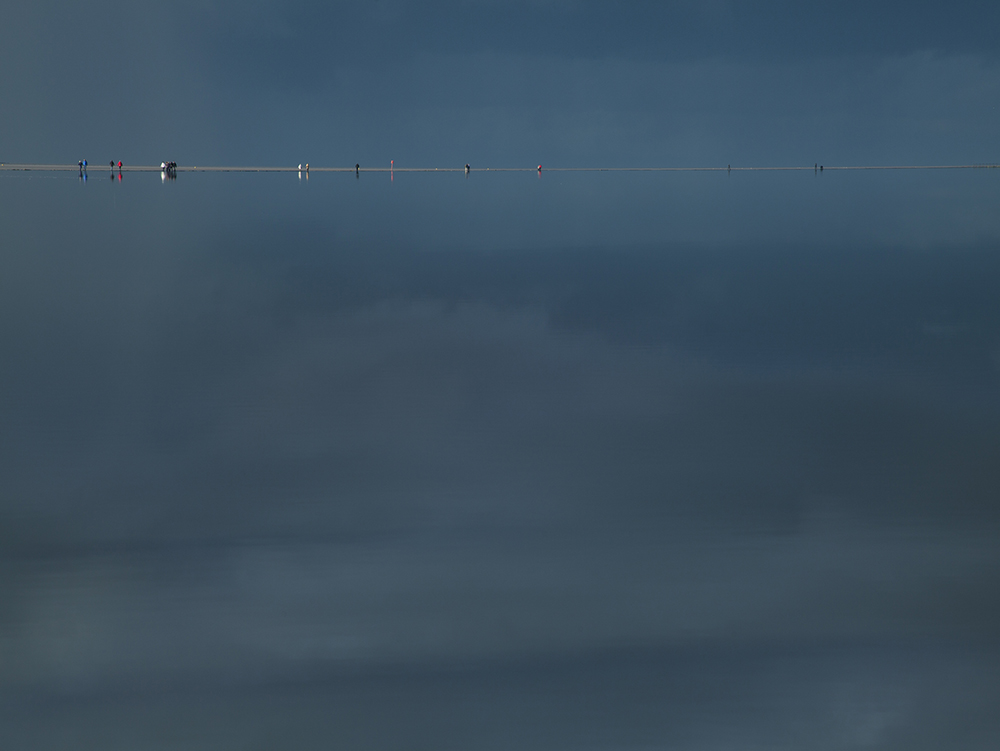

Is this the same marine lake you photographed for your prize-winning TPOTY entry in 2016?

Yes, I’ve been visiting regularly for the last ten years. I almost go there for the practise. It’s fascinating how the pictures you make there can reflect your mood or time of life. It’s more like the weather is photographing you than you’re recording the weather; you can take joyous pictures during storms or oppressive pictures on hot sunny days. It’s always the same but never the same, if you know what I mean?

And so close to home?

Yes, it’s funny, I’ve travelled all over the world for commercial clients but won TPOTY for images taken near my home and for two other series – one called ‘Dreich’ of bad weather in Scotland and another series I took of people at the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

How did you decide what to enter into TPOTY, it’s quite different from both your commercial work and social documentary projects?

Yes it’s very different to most of rest of my work. It’s stuff I haven’t necessarily seen other people do. I suppose I’m putting them out there to see what people think. It wasn’t so much that I thought people would love these photos it was that I love these things, I wonder if anyone else will?

You won overall in 2012 and were a category winner in 2016. What did winning do for you?

It changed things in lots of subtle ways I didn’t think about. No matter how long I’ve been doing this I still get a boost. It gives me confidence that allows me to go away and do the work I really want to do. In this instance it led directly to the ‘Fisherwomen’ project.

How did you end up becoming a photographer?

I originally studied physics at uni way back when, but I was interested in politics so photography, to me, was really a tool for communication. After I left uni, I spent a year travelling through north and Central America. I was interested in the politics of the region and went to Nicaragua during the first democratic elections after the Sandinista revolution. It was an extraordinary time and I came back with a portfolio of photographs that were quite newsworthy including a portrait of the president of the country.

I did a post-grad course in photojournalism once I got back and eventually applied for a staff job on the Independent. I think what swung it was that I had a portrait shot of a Guatemalan woman Rigoberta Menchu taken when she visited the UK. They didn’t know who she was. I told them she was going to win the Nobel Peace Prize. They were impressed; they’d never heard of her. And she did win.

What sorts of things did you get to shoot while at the Independent?

The role included covering press calls in Downing Street, IRA bomb blasts, hardcore news stories as well as portraits for the arts pages of notable characters like Doris Lessing. The 1980s were a very politically charged time and it was a great place to learn.

But everything is told in one picture in a newspaper and I really wanted to do longer form storytelling so this led to the idea of longer form personal projects.

Who are your key muses and inspirations in the photographic world?

I have always admired social documentary photographers like Gordon Parkes, Dorothea Lange and Paul Strand because they approach their subjects with empathy and compassion yet still have a sense of aesthetic. It’s the combination of purpose and artistry that leads to meaningful work.

What marks you out as being a good photographer is that it’s all about intent. At a time when everyone is a photographer or has a camera, at least, I’m thankful for people like Gordon Parkes who made work that was a visual record of a time. If we leave that up to the Instagram accounts of hundreds of millions of people it’s not going to be a considered history of our time. But going to live and work in communities and stay there for a length of time really allows you to have something to say. You can make beautiful pictures of pretty hard hitting stuff and that’s ok.

What advice do you have for photographers?

Oh, I’m still a student, myself, really. You never stop learning and that’s really important. I tell students that you don’t decide to do a long term project. If you start today, see if you’re still interested in a week’s time, two weeks’ time etc. Think of it in small chunks and see how long you remain interested. Some ideas lead you to places you’d never imagined and some have a natural end. The key is just to get started with an idea.

And on entering your work into competitions?

Haha, don’t enter what you shot last week because you always think your recent stuff is great! We all think our latest work is the best thing we’ve ever shot. But you need time for reflection. If you still like it in a month or two, it’s worth considering.

How do you shoot?

Of course, I use digital cameras for most of my commercial work but much of my personal work is still shot on film – specifically on large format film. I use a 10×8 field camera. It slows you down, you take different pictures. It’s a lovely piece of kit and you compose differently because the glass is upside down and back to front. For portraits it’s wonderful – I wonder if in a world where it is so easy to take a photograph with a phone or a digital camera, I get a different response from people when using a large format wooden camera. Just the sight of it and the effort that is involved in making the picture perhaps elicits a greater respect of the process from the people I’m photographing. It takes a long time to set up and that time is quite an intense moment in which you build a rapport with the person you are photographing. I just really like it, but as I say, it is just one tool I use for certain projects when appropriate.

More information on Craig Easton

Craig Easton’s Fisherwomen project is published by Ten O’Clock Books and the exhibition is currently touring the UK. Craig has just been crowned the overall winner of the Sony World Photography Prize for his series ‘Bank Top’.

You can see more of his work at www.craigeaston.com.