Part Two – From Above: The Majesty of Aerial Perspectives on Wildlife

Aerial wildlife photography has a magic all its own. It offers a perspective that is at once expansive and intimate – the world reimagined from above.

Personally, I’m especially drawn to images captured from helicopters. There is a visceral thrill in hovering over untouched terrain, looking down on ecosystems too vast or too remote to grasp from the ground. The patterns that emerge – winding rivers, intricate coastlines, shifting textures of land and water – turn nature into an abstract canvas. What once seemed ordinary becomes otherworldly.

“Family“ – Even the highly freshwater-dependent elephant families find a home among the sparse vegetation

Aerial photography has a unique power: it transforms the familiar into something extraordinary. The surface of a lake becomes a painting of light and sediment. Shorelines stretch like brushstrokes on a living canvas. Tiny animals become quiet symbols of fragility within the sweeping grandeur.

The emotional connection to the animal may feel less immediate in these images – they often appear small, secondary to the scale of the environment. But that’s precisely what can make the impact so profound. We see the whole – not just the creature, but the context. We see how life is embedded in landscape, and how vulnerable both truly are.

There is a certain detachment in this perspective, yes – but also a freedom. It invites us to step outside ourselves for a moment, to observe the Earth as a living, breathing organism. From this distance, we gain clarity. And perhaps, a new sense of humility.

This approach is particularly powerful in conservation storytelling. From above, we can reveal what lies hidden on the ground: deforestation patterns, disrupted migration routes, or the stark impact of climate change. It is a view that commands attention – and demands reflection.

A Long-Held Dream: Capturing the World from the Sky

Clockwise from large image: “Elephants Plains“ – In search of edibles; “Coastlines“ – Living Canvas; “Zebra Plains“ – An inhospitable area full of life.

The desire to capture photographs from the air — to see the world from a bird’s-eye view and document what is rarely visible from the ground — had fascinated me for some time. Naturally, the idea of getting a drone and using it to explore the surroundings from above quickly came to mind.

Drones: Practical but Problematic

But it’s not quite that simple. As practical and useful as drones can be for certain scenarios, they come with a range of logistical challenges and limitations. To start with, in Germany, most drones require a flight licence. Taking drones abroad can also be tricky — in many countries, their import is restricted, or at the very least, they prompt heightened security checks at the border. Additionally, their use is generally prohibited in national parks and private game reserves unless you obtain prior written permission. From an animal welfare perspective, this makes complete sense — the persistent buzzing of drones can cause undue stress to wildlife.

The Thrill of a First Aerial Shoot: Over Kenya in a Tiny Aircraft

So, it was a natural step to consider aerial photography from a small aircraft or helicopter instead. My first experience of flying in a small propeller plane over Lake Bogoria and Lake Baringo in Kenya was many years ago. The pilot kindly removed the door to avoid having to shoot through the usual scratched Plexiglas windows. While there was a brief safety briefing, there was unfortunately no photographic guidance. Sitting at the open doorway, secured only by a lap belt, camera in hand, I began to question my choices — and felt more than a little queasy. Still, the experience was incredible, even if the photographic results left much to be desired. I was overwhelmed by the impressions and unsure where to focus first — the flocks of birds in flight, the shoreline contours, or the patterns on the water. But my passion for aerial photography was well and truly ignited.

From Fixed Wings to Rotor Blades: A Helicopter Revelation

My first helicopter flight over Botswana’s Okavango Delta was an entirely different kind of flying experience. Initially, I was a little sceptical as to whether the helicopter’s movement would agree with my stomach. After all, nothing would ruin the moment more than constant nausea — or worse, vomiting mid-flight while circling flocks of flamingos. Fortunately, none of that happened.

I was fascinated by the helicopter’s ability to ascend vertically and hover in place, its agility and manoeuvrability offering the chance to photograph subjects from all angles — it made the whole experience a pure delight.

“Reflections“ – Dark volcanic hills reflected in the deep blue Natron Lake. Small clouds of salty foam dance on the surface, forming abstract patterns and splashes of colour.

The Aerial Perspective: Wildlife and Wilderness from Above

From the air, the vastness of this lush green and magically blue landscape truly comes to life. Some of the animal residents can only be properly observed and photographed from above. Even the mighty elephants appear tiny when seen foraging in the water below.

Fuelled by this fascination, I embarked on more extended helicopter flights across different regions of Kenya. Having the doors removed is now a must for me to capture quality images. Over time, a few essential principles for aerial photography have become second nature.

Salt Lakes from the Sky: Surreal Beauty in Harsh Terrain

I’ve been especially captivated by the stark and arid landscapes surrounding Kenya’s salt lakes, which reveal fascinating, almost surreal colours from above. Patterns and textures appear that are impossible to see from the ground.

Clockwise from large image: “Still Waters“ – Milky foamy salt steaks form bizarre shapes on the calm water surface of Lake Natron; “On Their Way to Mars“ – The shallow, highly alkaline water of Lake Magadi is rich in algae and microorganisms that give the water its blood-red colour; “Perspectives“ – Unreal shapes and lines open up new perspectives – are you in space or still on earth? The truth is hardly distinguishable.

Depending on the season and time of day, Lake Magadi and Lake Natron can glow in shades of turquoise green, shifting through blue and violet to nearly black. Milky, foamy salt streaks form bizarre shapes on the water’s surface, evoking something almost intergalactic. Elsewhere, polygonal, fiery red patterns emerge where the intense heat — often over 40–45°C during the day — causes the lakebeds to dry and crack. Sometimes, the dark volcanic earth shines through, creating a kind of spotted pattern.

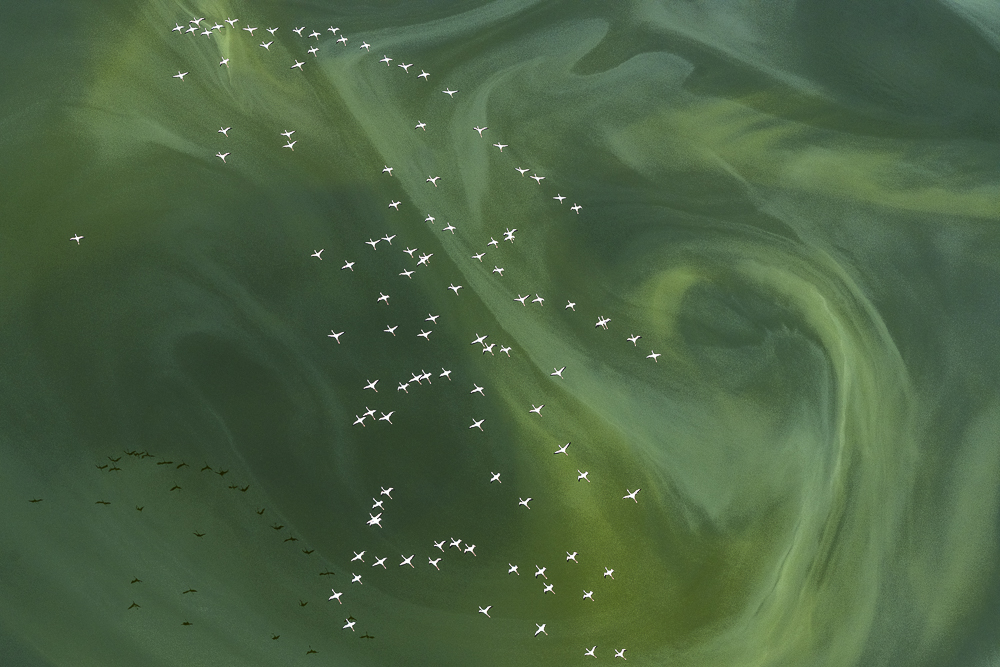

“Stay Where Your Heart Smiles“ – Large flocks of flamingos dance above the fascinating green water surface – their beauty and elegance enchant a smile.

These extraordinary colours are caused by bacteria present in the water. Though toxic and potentially dangerous to humans, these waters are a paradise for flamingos and other water birds. They filter the water with their beaks, extracting vital nutrients.

Clockwise from top left: “Blue Lagoon“ – The salty film on the surface almost seems like a blue lagoon; “Bubbles“ – Bubble-like patterns in iridescent colours form along the shoreline, like in a glassblowing workshop; “Gold Nuggets“ – Luminous veins of gold running through the surface – it’s easy to get caught up in a kind of gold rush; “Broken Hearts“ – As soon as the earth dries out, it breaks up and bright red hexagon structures form, reminiscent of broken hearts.

Dancing Birds and Living Landscapes

As you circle over the lakes in a helicopter, large flamingo flocks dance across the surface, forming abstract patterns. Pelicans gather along the shores, and the sparse vegetation reveals its intricate structures. Few places on Earth are simultaneously so hostile and so full of life. It was deeply moving — a harsh, rugged environment for survivalists, yet so fragile at the same time.

Left: “Dance of the Flamingos“ – For some inexplicable reason, the dance of the flamings leaves behind open spaces that constantly give rise to new patterns; Right: “Flamingo Paradise“ – A gathering along the water inlets.

Sadly, the impact of climate change and increasing human exploitation is becoming evident. Soda ash and salt are mined here — soda being Kenya’s most important mineral export — and these interventions are steadily reshaping the landscape.

Grey Skies, Golden Shots: The Beauty of Imperfect Weather

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned from these flights is that the “perfect weather” doesn’t always result in the best aerial photographs. On my first flight over Lake Magadi and Lake Natron, the weather was rainy and overcast. Initially, the flight was even at risk, as it wasn’t clear whether we could safely cross a nearby mountain range. In the end, thanks to our experienced pilot, we made it — and were richly rewarded with some truly unique images.

Left: “Lifelines“ – The water flowing into Lake Natron from the slopes of the surrounding volcanoes reveals the lifelines of the lake. Since Lake Natron has no outlet, the water can only escape through evaporation, and so nature conjures up breathtaking, almost unreal colours; Right: “Pangaea“ – The water veins and sandbanks draw patterns and shapes similar to long-gone continents. Maps that are constantly changing.

Rain had created tiny rivulets flowing down the volcanic hills, producing breathtaking colours. They resembled colourful lifelines, vividly illustrating how this region is sustained. These lakes are fed solely by runoff from the surrounding volcanic hills and have no natural outlet — all the water eventually evaporates, creating one-of-a-kind abstract artworks and striking photographs.

Beyond the Salt Lakes: The Rift Valley Revealed

Other parts of Kenya also reveal their true beauty only from the air. The lakes located north of Nairobi in the Great Rift Valley, while less desolate, are equally stunning. Lakes such as Bogoria and Solai are nestled among steep volcanic slopes and surrounded by lush greenery — and teeming with life. Large colonies of flamingos and pelicans call these places home. Once again, what seemed like poor weather conditions led to extraordinary photographic opportunities. Sediment-rich water flowing down from the hills not only attracted countless birds but also created images so unusual that, with a bit of imagination, one could mistake them for a map.

Left: “Dream Destination“ – Whatever continent you identify, it’s most likely a dream destination; Right: “Colour Explosion“ – Sediment-rich waters flows into Lake Bogoria and provides nutrient-rich water for millions of birds.

Lessons Learned in the Sky: Practical Tips for Aerial Photography

- Stay in the wind shadow: Never extend the camera beyond the helicopter’s wind shadow, or it will shake too much in the slipstream, resulting in blurry images.

- Use fast shutter speeds: Use a sufficiently fast shutter speed to compensate for the helicopter’s movement.

- Watch your aperture: Avoid shooting with a wide-open aperture in strong lighting, as it can cause a loss of detail in water textures or bird feathers.

- Watch your exposure: On sunny days, carefully monitor exposure to avoid overexposure and washed-out colours.

- Know your limits: If you have a sensitive stomach, think carefully before booking a helicopter flight — queasiness or fear of flying can ruin the experience.

Final Thoughts: Seeing with the Heart

In wildlife photography, perspective is more than a creative choice — it’s a feeling.

It reveals not just what is in front of the lens, but what lives behind it: curiosity, wonder, respect.

The classic view grounds us in the familiar. The aerial view lifts us into awe. The low angle draws us closer — into the quiet spaces where connection happens.

“Courage“ – A single flamingo struts through the shallow waters of Lake Magadi. The water level is so low that the volcanic underground can be recognized.

Each perspective holds a truth. Each image becomes a reflection — not only of the wild, but of how we choose to meet it – with patience, with humility, with heart.

In the end, the most powerful photographs are not just about seeing. They are about feeling. And remembering what it means to be part of something greater.

Read Part One… Silke looks at ground level and low level persp on the wild world.

To see more of Silke Hullmann’s photography visit her website

Or follow her on instagram @silkehullmann

Read other features on Eye for the Light about our planet and photographic techniques